Playlist: Classical Japan: The Tale of Genji (ca. 1021) by Murasaki Shikibu

Literary Salons at the Heian Court

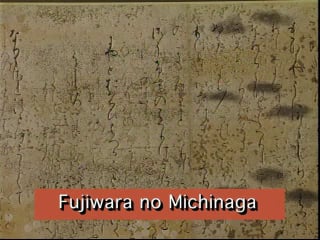

There was a great flourishing of culture in Heian Japan (794-1185) during the court dominance of the Fujiwara family. The Fujiwaras acted as regents to the emperors and increased their power by intermarriage with the imperial family. The outstanding instance is that of Fujiwara no Michinaga (966-1027), who married his daughters to four emperors and saw three of his grandsons become emperors.

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: It was in the Heian period, when the Fujiwara court was at its height, that the famous Tale of Genji was written.

Haruo Shirane: The Tale of Genji is the world's first novel, and it's written by a woman, Murasaki Shikibu, and she was a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court.

She served Empress Shoshi, whose father was [Fujiwara no] Michinaga. He was a regent, and the most powerful person of the time.

H. Paul Varley: ... Fujiwara no Michinaga, and he lived at the time of the writing of the Tale of Genji, and in fact, even made a sexual advance upon the author or authoress of the Tale of Genji, as she records in her diary.

Haruo Shirane: And Michinaga scoured the court to find the most talented women that he could find. And so she served Empress Shoshi. There was another consort, Empress Teishi, and she had a literary salon, and one of her ladies-in-waiting was Sei Shōnagun, the author of the Pillow Book. And so the Pillow Book and the Tale of Genji, the two great masterpieces of this period, and they come from competing literary groups within the same imperial court.

The Setting of The Tale of Genji

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: First of all it's about love, it's a romance. It's a male hero [Genji] who encounters many different women from many different social backgrounds. He himself belongs to the highest echelon of society. He's the son of the emperor, a member of the royalty. But the women that he encounters tend to be from lower ranks. And this is the setting, the social setting, for the Tale of Genji.

It's stream-of-consciousness in a way that's not found until seventeenth-, eighteenth-, ninteenth-century Europe. And that stream-of-consciousness, this pursuing of psychological, emotional, delicate intertwinings of the mind and emotions comes out of the women's literature. The men were more concerned with public affairs, with history. For the women it was their personal history, which was the ultimate history, and ultimately it was that personal history, the psychological description, that survived. We never read the histories by the men.

The Tale of Genji Introduces a Woman’s Point of View

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: The romances prior to the Tale of Genji were often from a male point of view — simply the male conqueror and his many conquests — but Murasaki Shikibu takes that same pattern, that same narrative paradigm, and looks at it from a woman's point of view, so that the problems that the woman encounters when becoming involved with a person of much higher status, looking at the lives of these various women, and most of all, looking at the problems of marriage.

I also think that the women had more time to think about these emotional, psychological aspects. After all this is what makes this the world's first novel is this ability to pursue the mind in the most minute ways, and that's why we call it a novel rather than simply a romance.

The Aesthetic of Impermanence

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: The notion of impermanence is an extremely salient characteristic of the Tale of Genji, of all the works of the Heian period. The notion that all things are ephemeral, that things must change.

On the one hand the aesthetics of the period are based on the beauty of impermanence — the scattering of the cherry blossoms, the dew disappearing before the sun rises. Even though it reminds us of the futility of the world, it's precisely that — it's the sorrow in the impermanence that brings us aesthetic pleasure. But toward the end of the novel, that becomes not simply an aesthetic pursuit, but a cold reality that turns the characters toward the other world and inward.

So eventually it becomes an inward quest. It starts as an outward quest for either other women or an outward quest for social mobility within society, but eventually it turns inward and becomes this internal quest for salvation, finding your own spirit. And that kind of foreshadows the great literature of the medieval period, which was the inward quest and the darkness outside.

The Impact of The Tale of Genji

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: Why was it that a work that was intended for such a small audience, such a small, elite society was to have such influence on Japanese tradition and culture and to become widely admired by a commoner audience?

Subsequent poets in the medieval period and in the Tokugawa period looked back to the Tale of Genji as, number one, the source of classical diction. This is the language that we should use. This is the pure Japanese that should be preserved.

Number two: It became the compendium for proper behavior, for aesthetic sensibilities. It was kind of like an encyclopedia of culture that poets who were both aristocratic and non-aristocratic looked back to. And when poets composed poetry, they drew the diction from the Tale of Genji, and they also drew their allusions, so if they would talk about some aspect of love, they might make a reference to some episode in the Tale of Genji.

About the Speakers

Robert B. Oxnam

President Emeritus, Asia Society

Haruo Shirane

Shincho Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture, Columbia University

H. Paul Varley

Professor Emeritus, Columbia University, Sen Soshitsu XV Professor of Japanese Cultural History, University of Hawai’i

Bibliography

The Bridge of Dreams: A Poetics of ‘The Tale of Genji’

By Haruo Shirane

Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988

Approaches to Teaching Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji

Edited by Edward Kamens

New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 1994

The Splendour of Longing in the Tale of Genji

By Norma Field

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987

“The Tale of Genji”

By Edward G. Seidensticker and Haruo Shirane

In Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective, edited by Barbara Stoler Miller

Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1994

Murasaki Shikibu: The Tale of Genji (A Student Guide)

By Richard Bowring

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, 2004

“The Tale of Genji as a Japanese and World Classic”

By Haruo Shirane

In Approaches to the Asian Classics, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom

New York: Columbia University Press, 1990

The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan

By Ivan Morris

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964