Playlist: Confucian Teaching

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao), Humaneness (Ren), and Ritual (Li)

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Confucian teaching rests on three essential values: Filial piety, humaneness, and ritual.

Irene Bloom: The Confucian value system may be likened in some ways to a tripod, which is one of the great vessels of the Shang and Zhou Period and a motif that reoccurs in later Chinese art. You could say of the three legs of the tripod, one is filial devotion, or filial piety. A second is humaneness. A third is ritual or ritual consciousness.

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao)

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Respect for one's parents, filial piety, is considered the most fundamental of the Confucian values, the root of all others.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: Almost everyone is familiar with the idea that filial piety is a prime virtue in Confucianism. It's a prime virtue in the sense that, from the Confucian point of view, it's the starting point of virtue. Humaneness is the ultimate goal, is the larger vision, but it starts with filial piety.

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Few of those who are filial sons and respectful brothers will show disrespect to superiors, and there has never been a man who is respectful to superiors and yet creates disorder. A superior man is devoted to the fundamental. When the root is firmly established, the moral law will grow. Filial piety and brotherly respect are the root of humanity.

Robert Oxnam: Filial piety derives from that most fundamental human bond: parent and child. The parent-child relationship is appropriately the first of the five Confucian relationships. Although the child is the junior member in the relationship, the notion of reciprocity is still key to understanding filial piety. The Chinese word for this is xiao.

[caption id="attachment_515" align="aligncenter" width="36"]![]() Xiao[/caption]

Xiao[/caption]

Irene Bloom: The top portion of the character for xiao shows an old man and underneath, a young man supporting the old man. There is this sense of the support by the young of the older generation and the respect of the young for the older generation, but it's also reciprocal. Just as parents have looked after children in their infancy and nurtured them, so the young are supposed to look after parents when they have reached old age and to revere them and to sacrifice to them after their death as well.

Excerpt from A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, Wing-tsit Chan, ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), Analects I:2.

Filial Piety and Ancestor Worship

Filial piety and ancestor worship are interconnected as parts of a single concept. This becomes clear when one considers that the word for filial piety is the same as the word for mourning. The child who acts with piety towards his or her parents is equated with the child who mourns his or her parents through the proper rituals.

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Filial piety, respect for one's parents, was directed both toward older relatives and ancestors.

Myron Cohen: A key manifestation of filial piety was ancestor worship. Ancestor worship in China was obviously related to the basic Confucian idea that children are obligated to respect their parents in life and to remember them after they have died.

There were two major loci of ancestor worship, as far as most people were concerned. One locus was in the home where people worshiped ancestral tablets. And the tablet behind me is an example of an ancestral tablet that would be kept in the home.

So this is the tablet of people named Liu whose remote ancestors came from this place called Peng Cheng, which is in Northern China. Below this the column says that this is the tablet or spirit tablet of the generations of ancestors of the Liu.

And this tablet in fact starts with the ninth generation and goes all the way down and you have the generations on either side going from top to bottom.

As I said, the large number of individuals in this tablet implies quite accurately that there are an awful lot of living descendants who relate to this particular tablet and who worship the ancestors in it.

Another important focus of ancestor worship was the graves. So that once or twice a year, minimally, people throughout China would go to the graves of their ancestors, both especially recent ancestors, but also sometimes more distant ancestors, to tidy up the graves and worship them.

Three Confucian Values: Humaneness (Ren)

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Another key value in Confucian thinking — the second leg of the tripod — is humaneness, the care and concern for other human beings.

Irene Bloom: A second, very important concept in the Analects of Confucius, and again in later Confucian thought, is that of ren. Sometimes that term ren is translated as goodness, benevolence. I prefer to translate it as humaneness or humanity because the character is made up of two parts.

On the left is the element that means a person or a human being. On the right the element that represents the number two. So, ren has a sense of a person together with others. A human being together with other human beings, a human being in society.

[caption id="attachment_517" align="aligncenter" width="43"]![]() ren[/caption]

ren[/caption]

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Confucius said: "...The humane man, desiring to be established himself, seeks to establish others; desiring himself to succeed, he helps others to succeed. To judge others by what one knows of oneself is the method of achieving humanity..."

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 6:28.

Three Confucian Values: Ritual (Li)

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: The last of the three central Confucian values is respect for ritual — the proper way of doing things in the deepest sense.

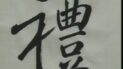

Irene Bloom: The third leg in this tripod is that of li — ritual consciousness or propriety. Li represents the forms in which human action are supposed to go on.

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Confucius said: "In rites at large, it is always better to be too simple rather than too lavish. In funeral rites, it is more important to have the real sentiment of sorrow than minute attention to observances."

Irene Bloom: In the character li, the strong religious associations are very, very clear here. On the left side of the character li is the element indicating prognostication or pre-saging. On the right, you have a ritual vessel.

[caption id="attachment_519" align="aligncenter" width="42"]![]() li[/caption]

li[/caption]

So while in the course of evolution of the Confucian tradition, li, rights, are considered to have become more, what in the West might be called more secular in character, not to be concerned so much with the idea of trying to appease deceased ancestors as had been true in the period prior to the time of Confucius. Still the notion of the ritual retains a very strong religious association throughout time.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: So as that evolves in a more secular, humanistic context, it still retains the sense that individuals have to defer to one another, have to show respect to one another. They have to be prepared to make some sacrifice for one another.

Myron Cohen: Confucius himself emphasized again and again that ritual itself was important. That rituals, that through ritual, people could learn proper relationships.

So if we look at ancestor worship through the lenses of ritual, what can we see? We can see, first of all, that through ancestor worship filial piety is eternal. People can continue to be loyal and obedient to their parents even after their parents have passed away.

At the same time, and in line, indeed, with the ancient Confucian theory, through ancestor worship, parents continue to teach their own children filial piety.

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 3:4.

Ritual In Everyday Life and Imperial Palace

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Ritual permeates all levels of social interaction in Confucian China.

Irene Bloom: There are all kinds of rituals governing all aspects of life, the great moments of life: Birth, capping (which is a coming of age ceremony for boys), marriage, death. So there are rituals also which apply to many other aspects of life as well, not just the great moments of human life but many of the smaller and more ordinary interactions of human life.

Robert Oxnam: At the pinnacle of the social order in imperial China was the emperor, the Son of Heaven, who performed rituals designed to preserve the cosmic order.

Myron Cohen: There was in fact a board of ritual, as part of the imperial government. And the emperor himself was deeply involved in ritual throughout the year.

The emperor, for example, there would be the annual worship of heaven, which was the most important day of the imperial ritual calendar.

Now it was not only heaven that was worshiped. It was also the emperors of previous dynasties that were worshiped, and it was also the ancestors of the emperor that were worshiped.

Insofar as the emperor was worshiping his own ancestors, he was being a good Chinese Confucian. He was doing what everyone else in China was doing. Insofar as the emperor worshiped the earlier emperors of earlier dynasties, he was proclaiming the continuity of the imperial institution, above and beyond the rise and collapse of particular dynasties. He was giving legitimacy to the imperial institution itself. Insofar as the emperor worshiped heaven, he was expressing his privileged position as the son of heaven.

Reciprocity and the Five Human Relationships

Transcript

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Zi Gong asked: "Is there any one word that can serve as a principle for the conduct of life?" Confucius said: "Perhaps the word 'reciprocity': Do not do to others what you would not want others to do to you."

Robert Oxnam: The importance of reciprocity, and the mutual responsibility of one person for another, is essential to understanding the five basic human relations suggested by Confucius.

Irene Bloom: Very prominent in the Confucian tradition is the idea of the five relationships. The relationship between, if you take it according to Mencius, parent and child, minister and ruler, husband and wife, older and younger brother, friend and friend. Those five relationships and the fact of human relatedness are of crucial importance in the Confucian tradition.

[The order of the five relationships is taken from that given by Confucius' most famous follower, the philosopher Mencius (active 372-289 BCE).]

Wm. Theodore de Bary: In the first four cases, you're talking about differentiated statuses. Now the point is not to necessarily confirm or reinforce the status difference but to understand what it is that establishes a responsibility between those two pairs in the relationship.

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 15:23.

On Government

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Confucius' overriding concern was with government. He believed that when virtuous men lead by moral example, good government would follow naturally.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: Then if we recognize that the issue at the start is what is the true vocation of the noble man or the noble person, it's a question of, "How do you govern? What is the proper way of governing?"

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Confucius said: "If a ruler himself is upright, all will go well without orders. But if he himself is not upright, even though he gives orders, they will not be obeyed."

Wm. Theodore de Bary: He says, "To try to order the people through laws and regulations and implicit punishments, if you do that, people will find a way to avoid, evade the law, and they will have no sense of shame. If you lead them by virtue and the rites, then they will govern themselves, discipline themselves, and they will have a sense of shame."

That's a rather basic statement of the Confucian appeal to a basic personal morality in all persons, all men, rather than a reliance upon coercion, on force, on power.

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 13:6.

The Gentleman

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Confucius sought to restore peace and order in China, such as that enjoyed under the Zhou dynasty, where leaders had been drawn from a hereditary aristocracy that governed according to certain traditions. Faced with the turmoil and change of his own day, Confucius held that the key to social order lay in the cultivation of the virtuous person, the moral leader, and he set about defining the attributes of the Gentleman, the Noble Man, who would lead society accordingly.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: Confucius is talking with members of this relatively leisured, educated leadership class. And he's addressing their concern as to what is the real meaning of being a noble person in very changed circumstances from those that originally gave rise to the tradition that he is working in.

The leadership class is also, they are also the educators, they are the teachers, they instruct the people, direct their activities. And there isn't any other significant class that performs this function.

[Excerpts from the Analects of Confucius]Zi Gong asked about the gentleman. Confucius said: "The gentleman first practices what he preaches and then preaches what he practices."

"The gentleman understands what is right; the inferior man understands what is profitable."

"The gentleman makes demands on himself; the inferior man makes demands on others."

Excerpts from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 2:13; 4:16; and 15:20.

On Education

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Implicit in the Confucian emphasis on ritual and self-cultivation through ritual is the notion that life is a continuous process of learning and self-improvement. Confucius stressed the importance of education for achieving personal and social order.

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]When Confucius was traveling to Wei, Ran Yu drove him.

Confucius observed, "What a dense population!"

Ran Yu said, "The people having grown so numerous, what next should be done for them?"

"Enrich them," was the reply.

"And when one has enriched them, what next should be done?"

Confucius said, "Educate them."

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 8:9.

The Classics

What were the Confucian Classics?

The Five Classics

The oldest listing of these dates from the second century BCE

- Book of History (Shu Jing) The historical records of the early Chinese dynasties.

- Book of Songs (Shi Jing) A sixth century BCE collection of lyric poems composed between ca. 1000-600 BCE.

- Record of Ritual (Li Ji) A guide to proper ritual behavior.

- Book of Changes (Yi Jing) A book of diagrams with interpretations passed on since the early Zhou dynasty for use in prognostication.

- Spring and Autumn Annals (Chun Qiu) The annals of the state of Lu, said to be recorded each spring and autumn, reporting significant events during the period 722-476 BCE (hence the name for this era, "Spring and Autumn Period").

The Four Books

These texts were added to the list of classics during the Han dynasty

- Analects (Lun Yu) The sayings and conversations of Confucius, collected by his followers.

- Great Learning (Da Xue) The concept of virtuous government with commentaries.

- Doctrine of the Mean (Zhong Yong) A guide, ascribed to Confucius' grandson, for achieving mental balance and harmony in one's life according to the Confucian principal of seeking regulation and moderation in all things.

- Mencius (Mengzi) The conversations of Confucius' most famous follower, Mencius, collected by his own followers.

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: Confucius often makes reference to what are known as "The Classics," a body of older literature and history compiled in his time. Confucius had great respect for the preserved wisdom of the past, and these classics became the basis for education in China.

Over time this canon was augmented by the Analects themselves and the writings of Confucius' followers. The Confucian Classics formed the curriculum for schools in China down through the nineteenth century. In imperial China the most prestigious career, that of government service, was open only to those who passed the rigorous examinations in the Classics.

Myron Cohen: So that in this sense, you can say that people imbibed with Confucian thinking and Confucian learning to a far greater extent than the ordinary person in China were in fact the rulers of China. And in a sense, this matched a basic Confucian value, which said that those who are educated have a moral obligation to rule.

So that, in that sense, you have a very powerful working out of the Confucian ideology via the examination system (and I'm referring to later imperial China), in terms of the actual ability of the state to govern.

Robert Oxnam: Familiarity with the Classics was widespread, supporting knowledge of Confucian ideals throughout Chinese society.

Myron Cohen: There were several ways in which these texts were publicized, so to speak.

First of all, there was the famous examination system in China, which selected both the bureaucrats for the government and also, confirmed people passing the exams at a lower level as being local leaders. In order to pass the exams, you had to have mastery of the Confucian text.

Therefore, study of the Confucian text was in fact incorporated in the basic curriculum of all village schools throughout China. And it's been estimated that in the late period of traditional China, approximately 40 percent of males had some literacy. This means that a very large percentage of the male population did have one or two years of exposure to Confucian texts.

Also, you had, at least in parts of China, you had traveling chanters who could chant Confucian texts, so that even people who were not literate at all had some knowledge of them. I don't think it is stretching the point to equate familiarity with Confucian texts with the kind of familiarity with the Bible that you had in the West in earlier periods.

Is Confucian Thought “Religious”? Confucius on Heaven and the Cosmos

The Chinese word for heaven or nature, tian, is pronounced tee-en with stress on the second syllable. In the character, the lower part is a character that by itself means "big." Adding the line on top is said to indicate that nothing is bigger than heaven.

[caption id="attachment_521" align="aligncenter" width="46"]![]() tian[/caption]

tian[/caption]

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: The question is often raised as to whether or not Confucian thought should be considered "religious."

Irene Bloom: As Confucianism is understood in the West, it often seems to come with a little tag attached saying, "This is philosophical and not religious." Which raises some very interesting questions about the nature of religion. What constitutes religion?

Wm. Theodore de Bary: According to Western conceptions of religion, primarily based upon the prophetic traditions of the Old and New Testament, or the Koran, certainly Confucianism is not a religion.

But nevertheless, Confucius has a very, very strong sense of reverence towards heaven, which is not distinguishable from a reverence towards life. You have a reverence towards life, and heaven is the source of life.

Irene Bloom: Confucius also draws on the authority of Heaven. The Chinese word, tian, can actually be translated either as heaven or as nature. But it has a sense of a moral order existing in the world, which governs all of human life and all of the processes of the natural world at the same time. Confucius says at one point, "Heaven gave birth to the power that is in me" — the power or the virtue that is in me. He seems to regard heaven as overseeing his life and the lives of others and overseeing, also, the cause of culture, so that there's a certain confidence here.

[Excerpt from the Analects of Confucius]Confucius said: "I wish I did not have to speak at all."

Zi Gong said: "But if you did not speak, Sir, what should we disciples pass on to others?"

Confucius said: "Look at Heaven there. Does it speak? The four seasons run their course and all things are produced. Does Heaven speak?"

Irene Bloom: Heaven does not speak, human beings have to discover the ways, the patterns, the order of heaven as it works out in the larger world of society and in their own lives.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: So what I would say is that Confucius and Confucianism have a very strong religious dimension, but they pretty much assume that the basics of religion are already given in the pre-existing tradition.

Robert Oxnam: This pre-existing tradition assumed that there is a cosmic order and that it is moral. Furthermore, this moral order was assumed to extend through the cosmos at every level — in heaven, on earth, and in human society.

Myron Cohen: The point is that these were not distinguished as separate domains, but as interconnected domains. It's this holistic interconnected, cosmic, integrated, entire view that I think is a fundamental characteristic of Chinese thought and Chinese belief in general, such that Confucianism fits into it.

For example, the basic Confucian ideas of filial piety — that children must be loyal and obedient to their parents, show them respect in life and reverence after they have died — these are not simply ethical ideas. These were ethical ideas given, if you will, cosmic validation. That a son should be respectful of his father was seen to be as much a part of nature as the rising and setting of the sun. So that ethical relationships were thought to be natural relationships.

Therefore, violating an ethical relationship would seem to be violating nature itself. The sanctions were natural, not supernatural, because in effect, you were causing disorder in the cosmos by violating ethical relationships. And this notion of the cosmos as containing important human relationships, as well as relationships and phenomena which we in the West might consider to be part of nature and distinct from human relationships, extended to many, many areas of thinking in China.

Excerpt from Sources of Chinese Tradition, Wm. Theodore de Bary, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960), Analects 17:19.

The Emperor and the Mandate of Heaven

Transcript

Robert Oxnam: The Chinese emperor was understood to be the "Son of Heaven" responsible for maintaining harmony between the human sphere and heaven. He ruled society with the "Mandate of Heaven."

Myron Cohen: The emperor as the Son of Heaven had received the Mandate of Heaven to rule society. The emperor, therefore, played a key role in linking the human social order to other domains of the cosmic order. Therefore, the emperor could be held fully responsible for disturbances in that order.

Wm. Theodore de Bary: The idea of the Mandate that one claims to have received from heaven is one that doesn't emphasize so much the confirming of one's authority as the importance of anyone who exercises or claims to exercise that authority doing so in a responsible way, responsible for the welfare of the people. So it really is a concept that imposes a moral test, a qualification, on the ruler, rather than accepting simply the claims that he might assert on the basis of either heredity or the acquisition of power.

Irene Bloom: This idea of course remains one of the most important ideas in all of Chinese political thought, right down to the twentieth century. When the students were demonstrating in Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989, one of their arguments was that the Communist party had lost the Mandate of Heaven. And so you can see this continuity over time from the early Zhou period from the eleventh century right down into our own time.

-

1

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao), Humaneness (Ren), and Ritual (Li)

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao), Humaneness (Ren), and Ritual (Li) -

2

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao)

Three Confucian Values: Filial Piety (Xiao) -

3

Filial Piety and Ancestor Worship

Filial Piety and Ancestor Worship -

4

Three Confucian Values: Humaneness (Ren)

Three Confucian Values: Humaneness (Ren) -

5

Three Confucian Values: Ritual (Li)

Three Confucian Values: Ritual (Li) -

6

Ritual In Everyday Life and Imperial Palace

Ritual In Everyday Life and Imperial Palace -

7

Reciprocity and the Five Human Relationships

Reciprocity and the Five Human Relationships -

8

Man Is a Social Being

Man Is a Social Being -

9

On Government

On Government -

10

The Gentleman

The Gentleman -

11

On Education

On Education -

12

The Classics

The Classics -

13

Is Confucian Thought “Religious”? Confucius on Heaven and the Cosmos

Is Confucian Thought “Religious”? Confucius on Heaven and the Cosmos -

14

The Emperor and the Mandate of Heaven

The Emperor and the Mandate of Heaven

Bibliography

The Analects of Confucius

Translated and annotated by Arthur Waley

New York: Vintage Books, 1989

The Four Books: Confucian Analects; The Great Learning; The Doctrine of the Mean; and The Works of Mencius

Translated and annotated by James Legge

New York: Paragon Book Reprint Corp, 1996

Sources of Chinese Tradition

Compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, with the cooperation of Wing-tsit Chan, 2nd edition

New York: Columbia University Press, 1999

A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy

Compiled and translated by Wing-tsit Chan

Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963

About the Speakers

William Theodore de Bary

John Mitchell Mason Professor Emeritus; Provost Emeritus; Special Service Professor, Columbia University

Irene Bloom

Anne Whitney Olin Professor Emerita, Columbia University

Myron L. Cohen

Professor, Department of Anthropology; Director, Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

Robert B. Oxnam

President Emeritus, Asia Society