Playlist: Tokugawa Japan: Bashō Narrow Road to The Deep North

Bashō the Traveler

Matsuo Bashō is commonly referred to by his given name, Bashō, rather than his family name, Matsuo. This is the custom with certain Japanese writers.

Transcript

Donald Keene: Bashō is known to the Japanese today not only because of his haiku, but because of the prose compositions he wrote.

The most famous of his travel accounts is his journey to the north of Japan, which, prior to this time, was considered to be a very unromantic place. It was a cold and desolate place. But because of Bashō, it is now the most popular object of pilgrimages, films, and so on.

Haruo Shirane: What's interesting about this is that Bashō at a certain point in his career started to take on the poetic persona of the traveler, of a particular kind of traveler, and that was the traveling priest in the Noh plays. [Noh is a traditional Japanese dramatic art form.]

And what happens in Oku No Hosomichi or Narrow Road to the Deep North, which is his great masterpiece, is that Bashō the traveler not only travels around Japan composing poetry and composing on everyday life, but he takes the pose of the traveling priest and encounters the spirits of the past. So he's traveling both geographically around Japan, as well as traveling back into the past.

Donald Keene: But, for him, going to these places was a stimulus for composing new poetry. It was an excitement at being in places which he had heard about but had never seen, and it was an occasion for composing some of his greatest poems. I think if you were to choose Bashō 's ten greatest poems, assuming there are ten greatest ones, I think at least six or seven of them would be ones that were composed on this journey.

[Excerpt from Narrow Road to the Deep North]Days and months are travelers of eternity. So are the years that pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives traveling. There are a great number of ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind filled with a strong desire to wander.

Excerpt from Yuasa, Nobuyuki, trans., The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, Ltd., 1966), p. 97.

Travel as Metaphor

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: In Narrow Road to the Deep North, the journey becomes the great metaphor. Travel is life. Life is travel. There's no end to travel; you die on the road, you're born on the road. And the road takes on several kinds of meanings. But it's a difficult journey, that's the narrow road. It's not an easy road, and the traveler is not just someone who's going sightseeing. He's someone who has cast aside all his belongings and basically becomes a beggar. And it's through that journey that he produces poetry.

Donald Keene: The account of the narrow road of Oku is short. It's only about thirty-five pages, and most is text, but it took him five years to write it. What this means, of course, is endless polishing, endless manipulation of the imagery until he was satisfied that he'd achieved it. And, as a result, it is the most popular work of Japanese classical literature. More people know this work than any other in Japanese literature. I don't think you can find a Japanese who has not at least had some exposure to it because of its peculiar attraction — the beauty of the poetry, the sensitivity to the different landscapes that he traveled across, and the atmosphere engendered by Bashō the man himself.

[Excerpt from Narrow Road to the Deep North]In this little book of travel is included everything under the sky, not only that which is hoary and dry but also that which is young and colorful, not only that which is strong and imposing but also that which is feeble and ephemeral. As we turn every corner of the narrow road to the deep north, we sometimes stand up unawares to applaud, and we sometimes fall flat to resist the agonizing pains we feel in the depths of our hearts. There are also times when we feel like taking to the roads ourselves, seizing the raincoat lying near by, or times when we feel like sitting down till our legs take root, enjoying the scene we picture before our eyes.

Excerpt from Yuasa, Nobuyuki, trans., The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, Ltd., 1966), p. 143.

Spritual Freedom

Transcript

Haruo Shirane: One of the reasons why Bashō becomes so fascinating for the Japanese is because he is someone who represents spiritual freedom in an era in which society is so hierarchical. We have society where the samurai are the elite, and the four classes, a Confucian hierarchy in extremely tight control over the populace. But Bashō is someone — at least the image he creates — is someone who is able to leave society. The recluse and the traveler become images of spiritual freedom.

Donald Keene: An almost saintly person living in an age when saintliness was not at a great premium, but at the same time being a part of that age, and yet transcending it by his poetry.

In 1993, which was the 300th anniversary of Bashō's journey to the north, the narrow road of Oku journey, there were millions of people, literally, who went to the same places. It was hard to get on a train. Everyone wished in some way to participate in this experience.

About the Speakers

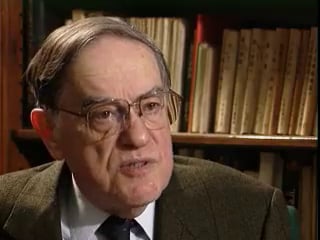

Donald Keene, University Professor Emeritus; Shincho Professor Emeritus of Japanese Literature

Columbia University

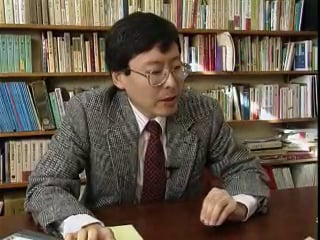

Haruo Shirane, Shincho Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture

Columbia University

Bibliography

Matsuo Bashō

By Makoto Ueda

Kodansha International, 1982

The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches

Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa

Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, Ltd., 1966

“The Poetry of Matsuo Bashō”

By Haruo Shirane

In Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective, edited by Barbara Stoler Miller

Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1994

Anthology of Japanese Literature: From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

Edited by Donald Keene

New York: Grove Press, 1960

“The Imaginative Universe of Japanese Literature”

By Haruo Shirane

In Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective, edited by Barbara Stoler Miller

Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1994

World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600-1867

By Donald Keene

New York: Columbia University Press, 1999

Related Videos

Tokugawa Japan: Bashō (1644-1694) – Master of The Haikai and Haiku Forms

Tokugawa Japan: Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725) – Samurai Playwright

Tokugawa Japan: Saikaku (1642-1693) – The Comic Novelist

Introduction to Tokugawa Japan